In 2020 and 2021, we all became well-acquainted with nasal swabs. But small sticks we stuck up our noses, it turns out, were harder to come by than anyone could have predicted. A May 2020 survey of 118 labs in the US found that 60 percent reported limited swab supplies – making lack of swabs the most commonly reported supply-chain problem.

One small company that stepped into the fray of swab production was the two year old OPT Industries, a Massachusetts-based company with fifteen employees involved in additive manufacturing (think 3D printing) of dense microfiber structures. The company’s printers and software can print more than just swabs, but the first product the company has focused on since 2020 is the InstaSwab – a 3D printed swab used in COVID-19 tests.

In four months in 2020, OPT Industries manufactured 800,000 nasal swabs for commercial partners like Kaiser Permanente and medical products distributor Henry Schein. After that trial run, the company foresees an uptick in production capability. Using newer, modular machines, Ou notes that each machine can now produce about 30,000 swabs per day.

“I think the pandemic has given us an opportunity to show a specific medical area where our technology can shine,” Ou tells TechCrunch.

While the pandemic is still a global disaster, the vaccines have changed the game when it comes to testing. OPT Industries is betting that it will survive a downturn in COVID-19 testing in the US by creating a superior swab, and pivoting to a home-testing market.

The pandemic was an early test-run for OPT, which at this point, has raised about $5 million in seed funding. The company is currently not seeking investment, notes founder Jifei Ou, but rather has moved into another testing phase for their swab products, the results of which were released today.

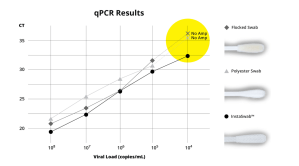

Statistics released today by OPT Industries, the company reports that on average their 3D printed nasal swabs were able to transfer 63 percent of viral genes into detection assays. Meanwhile in those tests, flocked fiber swabs transferred 36 percent and polyester swabs about 14 percent.

The performance of OPT Industries’ InstantSwab compared to two traditional swabs

These tests were performed at Boston University Medical Center, but the results were not published in a peer-reviewed journal (though Ou has more studies that are striving for this). They were also not conducted in human COVID-19 patients, but in vitro.

In theory, the InstaSwabs are better at picking up traces of the virus in the back of the nose and throat. Ou’s argument is that with the right type of swab, specifically, one designed with his dense microfiber structures, may help capture more of the virus and help prevent false negatives – Especially in the early days of infection, when there’s a lower viral load in the body to begin with.

There are countless studies looking to estimate the false negative rates for the litany of COVID-19 tests used. Case in point: one systematic review of 34 studies found estimates ranging from a 2 percent false negative rate to a 29 percent.

There is also evidence linking low viral load to false negatives. One study conducted at the Public Health Laboratory in Alberta Canada, analyzed 100,001 COVID-19 tests taken from about 95,000 patients (some patients were tested two or three times). Of that group, the authors were able to confirm five false negative test results.

The false negatives were attributed to low amounts of viral RNA in the body, which the authors note, was a factor of when the samples were collected. It’s not that the swabs missed the virus, it’s that there wasn’t much virus there to pick up in the first place.

When it came to analyzing how the swabs themselves influenced test results, the authors found that both swab types used by the laboratory had produced false negative results. Though that may imply that swab type didn’t influence false negative rate, the authors argue that more data was needed to reach that conclusion definitively.

That’s not to say that improving the way that samples are collected and stored can’t influence testing accuracy. One June 2021 paper argued that using less transport medium fluid (which would result in less dilution of samples) and redesigning swabs to pick up more virus and spend less time in patients’ noses could also help optimize testing.

What OPT will need to prove is that a superior swab can truly pick up significant amounts of viral RNA in the early stages of disease and that this greater pickup rate actually has an impact on false negatives.

While OPT Industries’ study (not peer-reviewed) seems to suggest the swabs can collect more virus, it doesn’t have enough information to prove that secondary thesis: that these swabs improve the accuracy of COVID-19 tests done in humans.

“We are right now working with two clinical partners to do clinical research on that,” Ou notes. “The result of this study and the result of the coming one will be combined together and we are preparing a manuscript to be published in a peer-reviewed publication.”

Should OPT prove that they can 3D print a superior swab, the bigger question is what market they’ll be poised to enter. As vaccines began to proliferate in early Spring of 2021, demand for Covid-19 tests plunged by about 46 percent nationwide, The Wall Street Journal reported (strangely, this didn’t seem to slow the explosion of testing startups, though).

The US is conducting an average of 504,048 new COVID-19 tests per day as of July 2021, down from an average of about 1,992,273 in January. (Even with the spread of the more transmissible Delta variant upon us, the CDC still notes that vaccinated people can refrain from routine testing.)

Ou still sees potential growth in the world of at-home testing – in this case, for COVID-19, though Ou notes that the company can 3D swabs for pretty much any bodily excretion that needs swabbing.

“One of the things that we’ll observe is that in the US, the majority of testing is shifting from a point of care or at a hospital to home testing. So this is our current focus and we’re looking at partnering and collaborating with the home testing kit company,” he says.

The company has secured “several” partnerships with home-testing companies, though an NDA prevents him from naming the companies, says Ou.

At-home testing in general (for both COVID-19 and other maladies) does have some interesting players entering the market, most recently, Amazon. Amazon plans to offer at-home testing kits for COVID-19 as well as STIs.

Perhaps OPT will be able to ride a new at-home swab wave beyond the pandemic.